Missed the homework assignment?

Show notes

7:50 | “That movie” is Look Who’s Talking (1998). At the end of this opening scene, a spermatozoon “talks”.

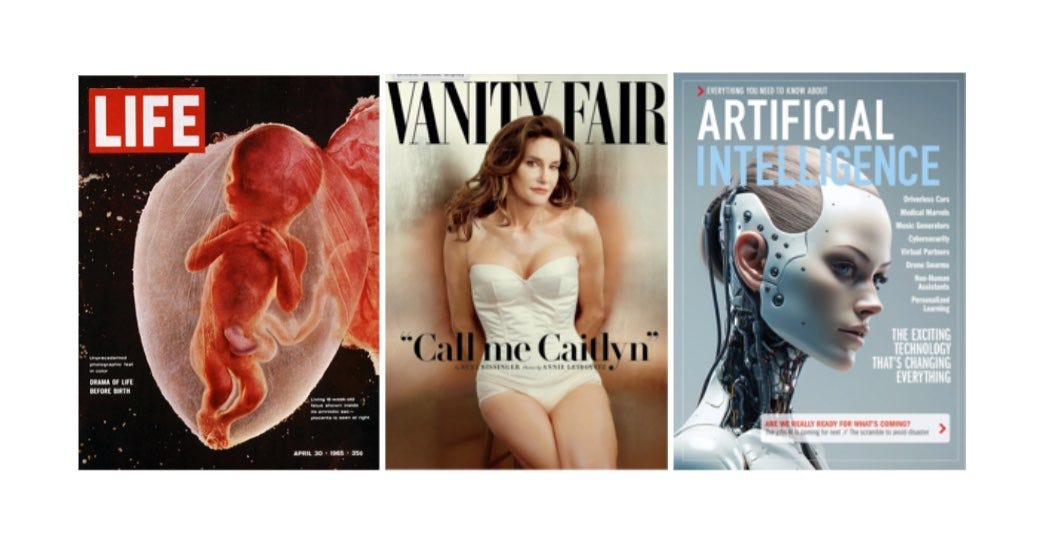

33:09 | LIFE magazine (wikipedia) started as a weekly humor magazine in 1883; in 1936, Henry Luce bought it and relaunched it as a general interest publication known for its photojournalism. It went to special issues only in 1972, before returning to monthly circulation between 1978 and 2000, when the last regular issue was published. Special issues continue to be published; last year, it was announced that Karlie Kloss will (once again) relaunch it.

27:50 | The book I’m Sorry For My Loss

33:30 | Lennart Nilsson’s photographs [Science Photo Library] [LIFE photoessay]

54:04 | Hyperallergic article about Esther Strauss’s sculpture “Crowning”

1:00:04 | Georgia couple awarded $2.5 million [NYT gift link]. George needs to read more carefully — especially when the details are even more relevant to the topic than she thought! This $2.5 million award is from a suit against the pathologist, Dr. Gates, they hired to do an autopsy: he was accused of posting pictures of the infant corpse on Instagram. Gates did not respond to the lawsuit, thus the plaintiffs received an automatic judgment, after which the damages were decided by a jury. Gates has indicated he will appeal the damage award. The couple has a separate lawsuit still pending against “the obstetrician, Dr. Tracey St. Julian, as well as Southern Regional Medical Center and six unnamed nurses”.

1:01:30 | What was pre-modern birth like? This book looks interesting: History of Childbirth: Fertility, Pregnacy and Birth in Early Modern Europe

1:02:05 | Illich on “delivered” referring to the woman, not the child

The womb was declared public territory. The exercise of midwifery was made dependent on formal instruction and continual medical supervision. This transformation of the experienced neighbor into a licensed (and otherwise illegal), specialized accoucheuse was one of the key events in disabling professionalism. And this change was reflected in language. Childbirth ceased to be an event of and among women. The womb, in the language of the medical police, became the specialized organ that produces infants. Women were described as if they were wombs on two feet. Women no longer helped other women deliver; the doctor or midwife delivered the child. (link).

The titled footnote (87) that follows soon after this paragraph is called “From the Delivery of the Mother to the Delivery of the Child”

1:03:05 | “We Are Repaganizing” by Louise Perry (First Things)

1:15:15 | Minnesota shooter’s “pro-life” motives (Mother Jones).

1:15:50 | Anti-choice violence in the US (wikipedia)

1:22:30 | Bryan Johnson trying to live forever (Time)

1:22:58 | Mary Harrington, “Pray for Albion” (22 June 2025)

1:23:10 | On the abortion case that motivated the UK’s recent decriminalization of self-abortion at any fetal age (NYT gift link):

(Gemini AI Summary) In June 2023, Carla Foster, a mother of three from Staffordshire, was initially sentenced to 28 months in prison for illegally procuring her own abortion at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. She had taken abortion pills when she was between 32 and 34 weeks pregnant, after ordering them through the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS). The case drew significant criticism and outrage, with calls for compassion rather than punishment, particularly given the circumstances of the pandemic and the fact that abortion is legal in the UK up to 24 weeks. The Court of Appeal later reduced her sentence to 14 months, suspended, and ordered her to complete 50 days of activity.

1:29:12 | Dara Horn, People Love Dead Jews. Read it!

Quotes

Losing the horizon

[A]mong the invisible, the unborn, which is invisible in the body of a woman, is an important historical subject. Two things distinguish it from others of its kind. It is never there with certainty; in spite of many signs and intimations of its presence, one can never be sure about it. Unlike the dead, one’s guardian angel, or God, it cannot be grasped by faith; it remains a hope. And second, before a child comes to light it is a nondum, a “not-yet.” It has a peculiar temporal dimension. It is the only one of the invisible beings that knocks at the door of existence and emerges as an infant.

It has become very difficult for us today to realize, to sense, the horizon beyond which the not-yet was hidden for most of historical time. One of the most fundamental but least noted events in the second half of the twentieth century is the loss of horizon…It was just yesterday that the whole earth suddenly “appeared” as the Blue Planet and we began to accept the fact that all would be exposed to recording equipment orbiting far above this Tower of Babel. I regard the fetus as one of the modern results of living without a horizon.

[The unborn] is closely tied to the history of hope. But when hope is dissolved into expectations that can be managed at will, scientifically, sociologically, and arbitrarily, the unborn is no more. (6-10)

The seen and the shown

We are told what to see; we are told that these clouds and masses [the blastocyst images] were recorded by a scanning ultramicroscope and that they represent a human being. Our readiness to see on command has grown tremendously in the intervening twenty-five years… This popular exhibition of fetoscopy spoke powerfully about the desire to dissolve the frontier between the viewer’s eye and the unborn. It effected the breakdown of a horizon which, since the beginning of history, had made the unborn an unseen and unverifiable presence. [...] Fetoscopy…solicited the viewer to join in an immodest adventure like a peeping Tom. The Life magazine of 1965 panders to the libido videndi, the ravenous urge to extend one’s sight, to see more, to see things larger or smaller than the eye can grasp—to see things which have previously been off limits.

[...]

We have gotten used to being shown no matter what, within or beyond the limited range of human sight. This habituation to the monopoly of visualization-on-command strongly suggests that only those things that can in some way be visualized, recorded, and replayed at will are part of reality. [...] The result is a strange mistrust of our own eyes, a disposition to take as real only that which is mechanically displayed in a photograph, a statistical curve, or a table.

[...]

Losing a real horizon, we have lost [the] sense of obscurity. Through immodest revelations—for example, the skinning of woman’s body—we have lost the power to discriminate between the seen and the shown. We have gotten used to a world of confused figments where, for a churchman, a vague clump is a persuasive argument for “a life made in the image and likeness of God.” The Great Potter’s clay has been turned into a montage programmed by a genetic code. (12-19)We are told what to see; we are told that these clouds and masses [the blastocyst images] were recorded by a scanning ultramicroscope and that they represent a human being. Our readiness to see on command has grown tremendously in the intervening twenty-five years… This popular exhibition of fetoscopy spoke powerfully about the desire to dissolve the frontier between the viewer’s eye and the unborn. It effected the breakdown of a horizon which, since the beginning of history, had made the unborn an unseen and unverifiable presence. [...] Fetoscopy…solicited the viewer to join in an immodest adventure like a peeping Tom. The Life magazine of 1965 panders to the libido videndi, the ravenous urge to extend one’s sight, to see more, to see things larger or smaller than the eye can grasp—to see things which have previously been off limits.

[...]

We have gotten used to being shown no matter what, within or beyond the limited range of human sight. This habituation to the monopoly of visualization-on-command strongly suggests that only those things that can in some way be visualized, recorded, and replayed at will are part of reality. [...] The result is a strange mistrust of our own eyes, a disposition to take as real only that which is mechanically displayed in a photograph, a statistical curve, or a table.

[...]

Losing a real horizon, we have lost [the] sense of obscurity. Through immodest revelations—for example, the skinning of woman’s body—we have lost the power to discriminate between the seen and the shown. We have gotten used to a world of confused figments where, for a churchman, a vague clump is a persuasive argument for “a life made in the image and likeness of God.” The Great Potter’s clay has been turned into a montage programmed by a genetic code. (12-19)

The tailor’s wife

The body historian wants to know what it felt like to be alive 250 years ago, but only slowly does she come to hear how women spoke about their embodiment back in the time of powdered wigs…What I read is so strange that I must struggle against disbelief before I am able to take these women at their word. (62)

[And then she goes on to describe the experience of the Tailor’s Wife, in a small town in Germany in 1724, who visits her local doctor, Dr. Storch.]

The woman complains that since Christmas her “monthlies” have been stuck and that, at a certain point, she imagined herself pregnant. We must not forget that seven generations ago, pregnancy was much more common than it is today. On any given day of the year, a significant number of all women between seventeen and forty in this part of Thuringia imagined themselves pregnant… The symptoms of pregnancy on which modern women base their belief are different from those of Storch’s patients.

[...]

Blood is neither an argument against pregnancy nor a reason to be particularly upset. Yesterday, however, the flow increased so much that she swooned, and today she noticed that something leathery also left her with the blood, whose flow did not decrease. Today, when the menses stop for four months, most women would know if they are pregnant or not. What the Tailor’s Wife describes appears to us like the story of an abortion, and we would look for a fetus in her discharge. We would worry that this poor woman might be suffering shock… She calls the thing which left her something leathery…something made up of skins. I have collected the words women use when they talk about this: they speak of “blood curds,” “wrong growths,” “burnt-out stuff,” and “singed blood.”

[The woman has continued to have labor pains; Dr. Storch prescribes a drug for accelerating birth, and the next day she delivers something that looks like afterbirth.]

I cannot categorize this event by our standards. I do not know if this was a spontaneous abortion or the result of several weeks’ effort on the part of the woman’s mother to loosen the menstrual congestion of her daughter, or if the woman herself had used one of the strong abortifacient potions that every woman would know… [Storch] places her in the same category as the many other women who occasionally bring forth not children but other kinds of fruits. In Storch’s view, the physician, like the gardener, lends his support to nature, and nature in Storch’s sensorium is very active. …Storch sees nature at work in the womb, expelling what is untoward rather than aborting what should have become. The whole process of generation in Storch’s writings is ambiguous. It can go wrong from the very beginning.

According to our witness conception, from carnal mingling to the moment of birth, is Janus-faced. It could be “true and real” and lead to the timely appearance of a child, or “wasted, empty and useless” — a falsum germen that nature must purge and, from the doctor’s point of view, whatever it might be, it is a not-yet; it is of uncertain issue. It makes no sense to interpret this luxuriant growth of untimely fruits that issues from an organ in need of constant purging with categories now current in bioethics, or feminist or political discourse. (62-66)

A redefinition of Christian “life”

All Christian denominations place great importance on baptism. In the major churches infant baptism has become the rule, and in the Roman Catholic church there is a well-established tradition imposing on everyone the duty to baptize a newly born infant in danger of death. From the end of World War II well into the 1960s, the church’s new concern with the fetus was reflected in a novel set of instructions. These ruled that every Catholic nurse should sprinkle water on anything she suspected might be a spontaneous abortion. While doing this, she was to pronounce the conditional formula of baptism, saying, “If you are human, I baptize you…” (60? thereabouts?)

Duden stresses that this idea of pastoral care for the non-living and the unborn is actually utterly novel:

In most of the New Testament and in two thousand years of ecclesiastical usage, to “have life” means to participate as a believing Christian in the life of Christ, a mode of living which is placed in stark contrast to mere human existence. Even the dead live in Christ, and only those who live in Christ have life in this world. Of those who exist outside this relationship, the Church has consistently spoken as those who “live” under conditions of death. In this sense and only in this sense is life holy and can one speak of the sacredness of life. This is simply the traditional understanding and teaching. (101)

Illich’s “To Hell with life!” speech, via David Cayley’s biography

Campbell told [Illich] that he feared that the question of life was “tearing our churches apart.” On issues like nuclear disarmament, abortion, capital punishment, and ecology, he said, Christians were at each other’s throats. He then asked “his great favour.” If he assembled a meeting of church leaders, would Illich come and address them on the subject of life? Illich was immediately apprehensive but bound by his promise to obey. He agreed. The meeting took place within the year in Ohio. The atmosphere was tense. A representative of the Catholic Bishops Conference who was present urged Illich to begin with a mollifying prayer. Illich instead began with a solemn curse. Raising his hands, he repeated three times, “To Hell with life!” This dramatic ceremony began Illich’s engagement with what he would later call “the most powerful idol the Church has had to face in the course of her history.” It was not an issue on which he was ever able to make himself widely understood. (314)

Equal opportunity abstraction

While the whale, the rain forest, the terminal Alzheimer’s patient, the spina bifida infant, the botched suicide, and those affected by Karposi’s sarcoma constantly emerge from a mixed bag of threatened lives, life itself finds its principal visual expression in two complementary disks: on the one hand, the Blue Planet, on the other, the transparent pink zygote. This pair has moved to the top of the list of cult objects in the 1990s. (99-100)

[...]

Any criticism [of how the word “life” is used] is immediately answered by someone who connects life with right or value or sacredness and, by doing so, evokes six million Jews, or sixty million fetuses, or large numbers of Kurds and Cambodians, or even the rain forests, bugs, and grasses. The four-letter word is meaningless and loaded; it can barely be analyzed, yet it is a declaration of war. (104)

Share this post